I mention in my previous post one of the few things I’d so far been unable to fabricate for the child printer has been extruder gears. Yes, attempting current generation extruder gears with a 0.8 mm nozzle diameter results in nothing short of a blobby mess. It was clear that a self reproducing filament deposition machine could not easily exist in a scavenging society unless its nozzle was of sufficient resolution to print its own gears. This placed the nozzle squarely in the place of a bottleneck. While I had previously tested the first iteration of my hot end with 0.6 mm diameter, this solution was found to clog soon after anything of legitimate size was printed. As a result, I would conclude the nozzle needed to be reworked, from scratch.

This was not the only reason to rework the nozzle, however. The nozzle as it then stood was finicky between prints, and required long bouts of troubleshooting where the toaster wire was repeatedly removed and reinstalled to access the rest of the nozzle. This no doubt placed stress on the insulation used to guard the toaster wire from short circuits. Once, after a long session of troubleshooting I restarted the printer to find the toaster wire I’d used as a heating element start to short out, glowing red hot before briefly combusting the kapton tape, then overloading the PSU’s fuse and effectively shutting itself down. The event lasted no more than a second or so and was over before I’d reached for the off switch. With the heating element toast, it was pretty clear a new nozzle was needed.

Before continuing, let me say: I know full well that pre-fabricated hot ends are readily available off the internet for the right price. Still, I remain a dogged post-apocalyptic cheap skate. Nothing on the market at present is completely outside the reach of the common man, at least in function, and at the very least the machines used to make the hot ends can themselves be machined. Concessions are necessarily to ensure failsafe operation, but overall these concessions could still be limited to purchased components which could still in theory be procured from scavenging old parts, e.g. heating elements.

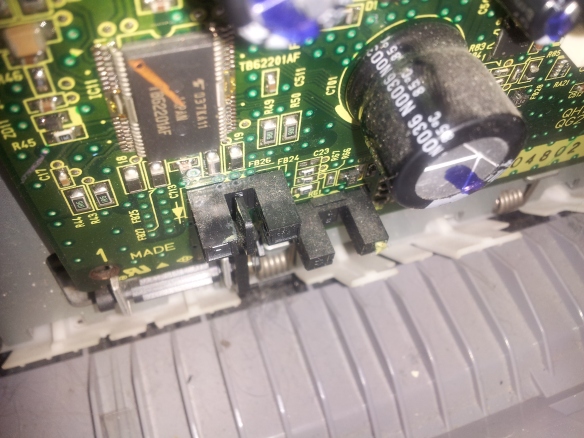

With that in mind, I’ll start off by outlining the needs I considered in designing the new nozzle. First, it was clear a heat resistor would be used in place of toaster wire. A heat resistor is inherently immune to short outs and would always provide a reliable resistance and wattage density, making it far safer than any toaster wire ever could be. A heat resistor, however, is a bulky thing, and using one would require a custom made heat block to hold it. Barring this, it could be that the entire nozzle would have to be custom made. Still, having only a drill press in my carpenter’s work shop I wanted to make sure these components could be fabricated without the help of a lathe.

Secondarily, I ideally wanted an all metal design which could enable printouts from material with higher melting points such as ABS and polycarbonate. This is a demanding task, though, and if need be I was willing to suffice with a metal hot end bearing a thin teflon lining to lubricate the filament through the isolator, much like the successful J-head nozzle. Doing this would at least remove the need for ordering thick rods of PEEK or Teflon from the internet. In either event, an nozzle made almost entirely from metal would require some sort of heat sink to act as a thermal break, possibly even requiring a fan.

There were still a dizzying number of diy hot ends on the reprap wiki which could fulfill these objectives, however none did quite exactly what I needed. Many, I found, required drilling long, straight holes through solid stainless steel threaded rod or carriage bolts in order to make a steel isolator. The kettle hat nozzle is a good example of a nozzle I tried like this. I tried a few good days trying to get holes such as this. Some limited success was had, but in the end none of the holes I drilled got anywhere near the length needed to support an isolator, heating block, and acorn nut nozzle tip. Even if I were successful in drilling a hole this length, I was very uncertain the process could be repeated for other diy-ers with their own drill press and work shop.

That was when I started to rethink these designs. Previously, I was working off the assumption the nozzle tip would be the most difficult component to machine since it required drilling through a block just far enough to the other side that you could drill the remaining way with a flimsy bit less than a millimeter in diameter. If the remaining wall was too thick, the small drill bit would likely break before any progress was made. In my previous nozzle design this led me to create my nozzle as is frequently done from an acorn nut.

Nevertheless, after very little effort I was able to drill my own custom made nozzle tips from blocks of aluminum. Going this route also allowed me to couple the heater block with the nozzle, saving space as well as reducing a extra joint at which leaks could occur. At the same time, I was finding it much harder to drill long distances through threaded rod in order to make the isolator. Given these findings, I refocused my design to make the isolator as easy to fabricate as possible. On a chance visit to hobby lobby, I found a good collection of metal tubing which could act as a pre-fabricated isolator:

Tubing was available for many diameters in aluminum, copper, and brass. The 2mm diameter tubing fit perfectly with the teflon lining I’d already purchased for my previous nozzle iteration. I also chose the brass tubing given it has the lowest thermal conductivity of my three options. If any are hoping to replicate this nozzle, steel would be an even better choice assuming its available in your area.

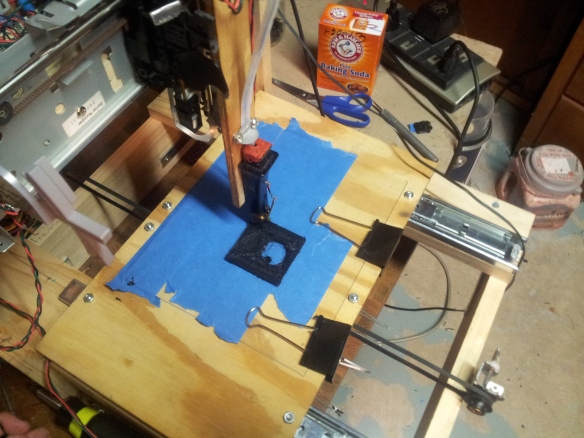

A second heat block/nozzle tip was crafted that resembled the ones I’d tried with threaded rod, however this time around I drilled a hole that matched the diameter of the tubing I’d gotten from hobby lobby. The fit was intentionally made snug enough such that I had to bash the brass tubing into the heat block/nozzle tip with a rubber mallet (careful not to use a regular hammer – I’m quite certain it would bend the tubing!).

The heat sink I attached to the nozzle was originally meant to cool a series of mosfets in a computer I’d taken apart. It serindipitously fit snugly with the 2mm isolator I went with, however just in case it should come loose I tightened it further in place with a screw whose diameter roughly matched the distance between the rills in the heatsink. The contraption holds very steady without requiring any holes to be drilled in the heatsink.

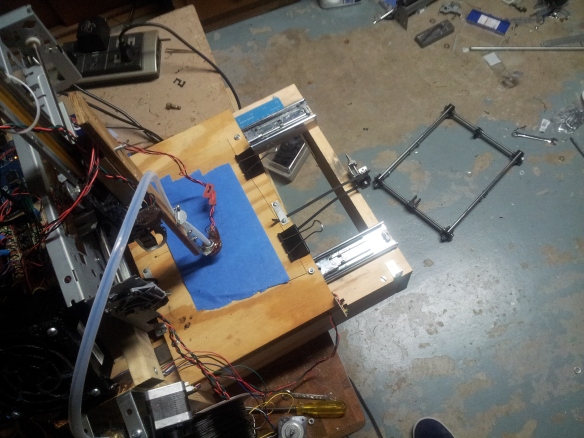

I tested the contraption on a printout of a star trek commbadge (shown here). At a few points when calibrating z-axis offset, I set the nozzle too low and crashed it into the bed. I was worried in this event the metal tubing would be flexible enough to bend out of shape, however after a few times of this occurring I believe its safe to say this does not occur.

A bigger issue occurred as I scaled up print size – the heat sink would saturate with heat and cause the filament to melt too early, in turn jamming the nozzle. I had anticipated this problem, however, and it was quickly resolved by screwing a scavenged pc fan to the heatsink.

Now the heatsink is just a few degrees above room temperature, and the only limit to size now is the build space!

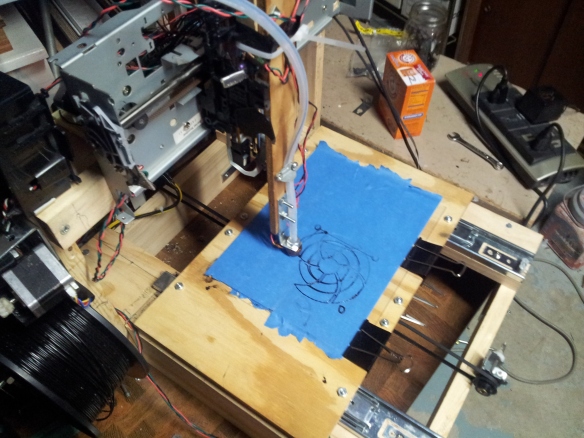

Shown below is the printer fabricating the chuck to a printable lathe, which will hopefully go on to further simplify hot end creation. In time, I hope to write up an article on the reprap wiki to document the design, with plenty of pictures to document the process. Switching out the drilled out threaded rods can definitely simply the construction of metal hot ends in the future.